- damnonia.blue

- saints way

- devonshire

- tamar

- tavy

- dartmore

- constantine

- around bartons

- svaqquci

- exmoor

- somerset

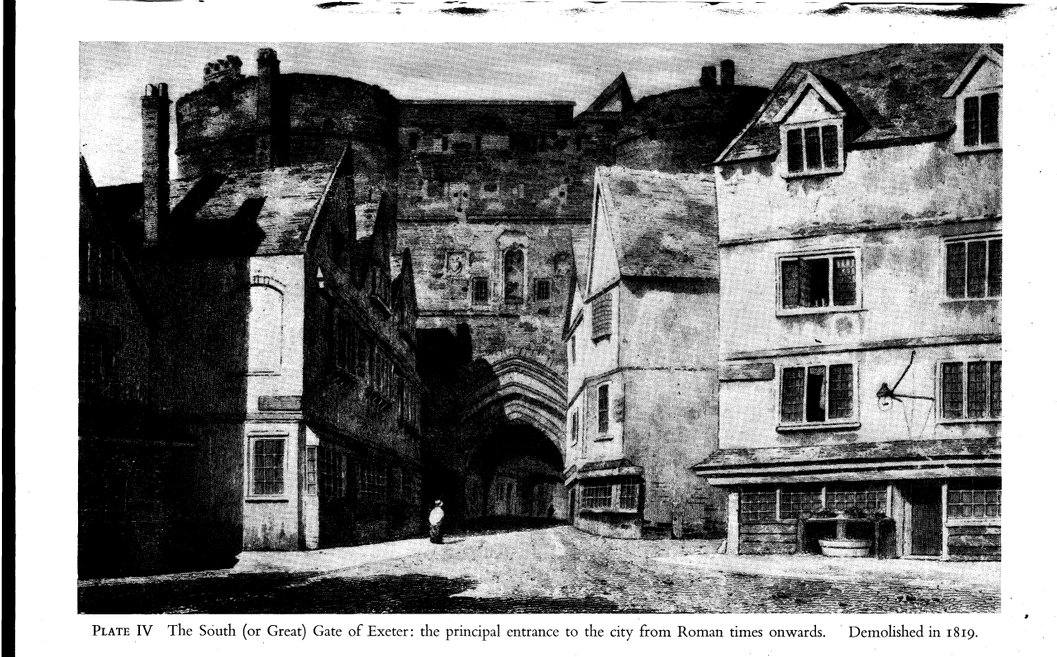

- eXe

- totenesium

- halge wylle

- taintona

- iscas waterways

- severn sea

- pearls

- highways and biways

- bodmin more

- duchy of

- cornwall

- the tin islands

- mendip

- sea mills bristol

- saint anne

- avon

- aXium

- waelas

- saxon

- uplyme mystery

- green stones

- many magicians

- rud hud hubridas

- March25AD33

- lynher