The “ Dead lane ”

Ancient Roads and Tracks

17

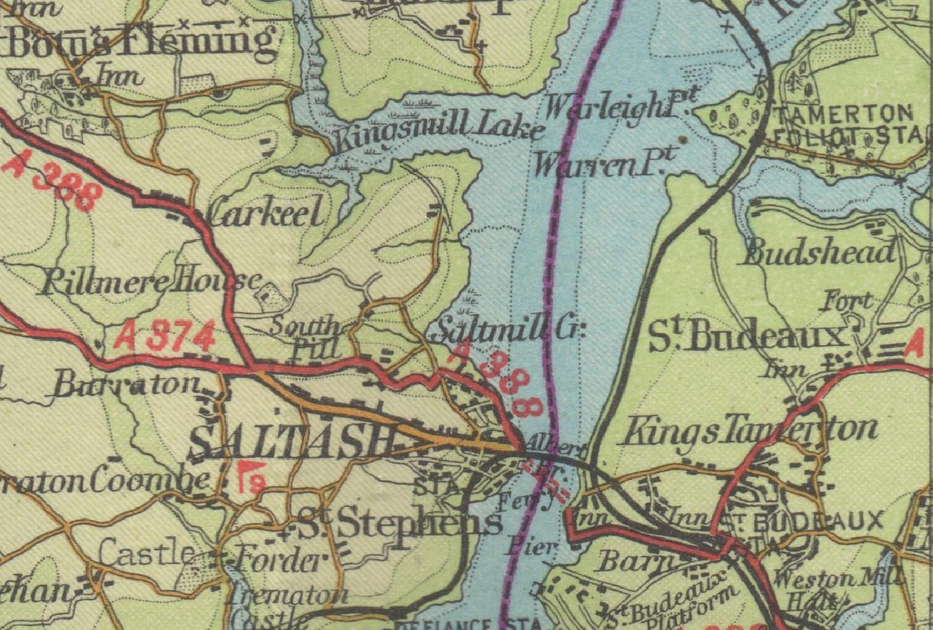

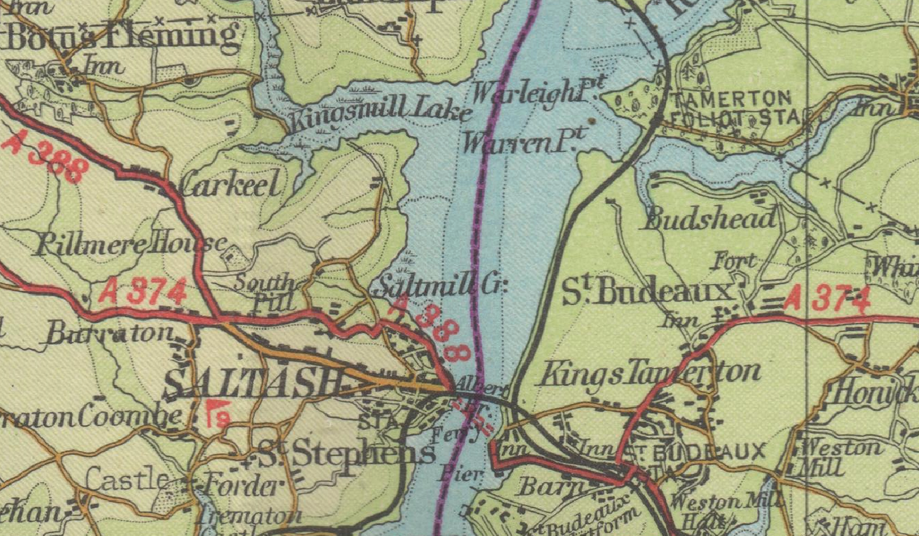

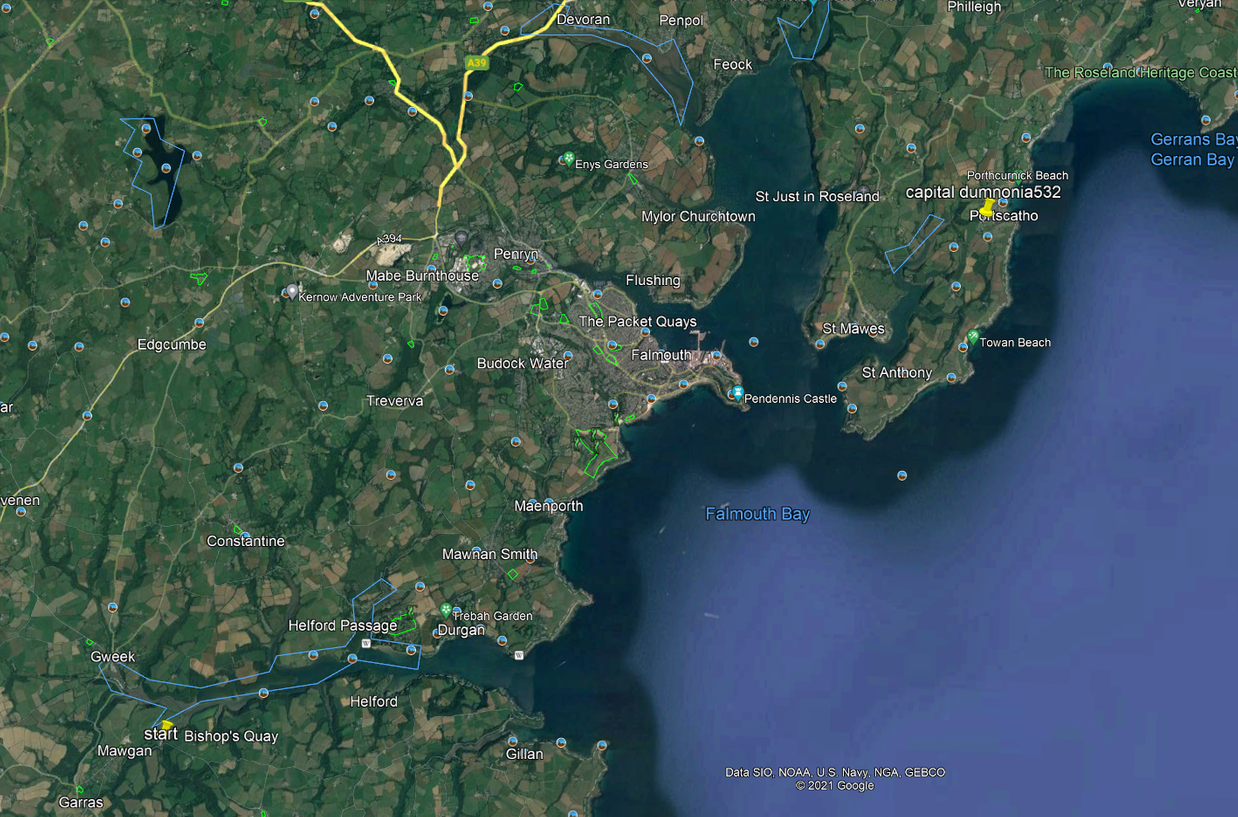

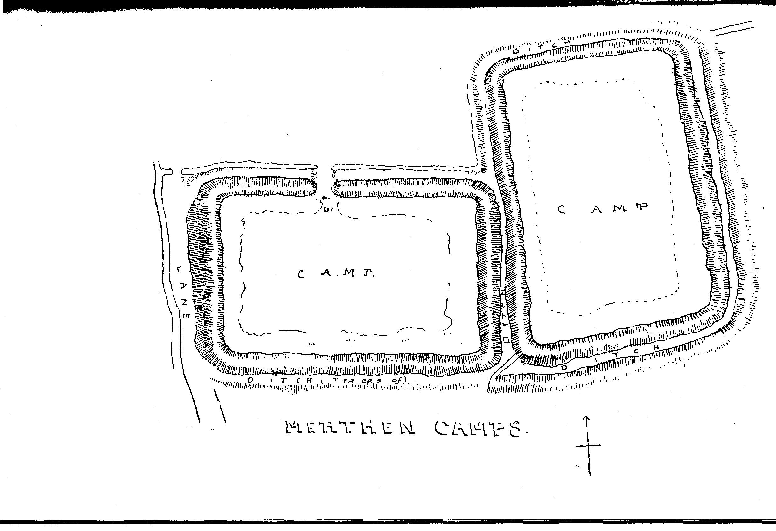

The third ancient ridgeway is that coming from the Quay at Merthen Hole, up through the woods, across the old deer park, where it passes through the ditch of the earthworks, so out over the Downs, across the fields to Brill.

Then to Trewardreva and over the ford (Ret) which gave name to Retallack.

So up the hill along past the site of Maen Rock , skirting Treworvac , across the fields to the “ Dead lane” , where it proves its antiquity by being a part of the parish boundary, then into the Lestraines lane and out to the Turnpike from Helston to Truro at Rame.

The “ Dead lane ” is a strip of this ridgeway which has not been used for over a century, and is so called because it is now a cul-de-sac.

On either side of it is a tumulus, for barrows, like ancient roads, are found on ridges. It is remarkable that this lane, about three-quarters of a mile in length, is the only piece of road which forms part of the Constantine parish boundary.

All the rest of the boundary is formed by creeks , streams, or, for a very small distance, by hedges .

At Merthen Hole it is a typical pack-horse track cut out of the rock . Its paving stones remain beneath the fields and make ploughing Impossible.

The fourth main ridgeway is the present main road from Penryn, entering the parish near Bossawsack and continuing past High Cross down to the river atCalamansack.

There are two principal tracks across the parish from east to west, 2nd as the lower has to traverse six deep valleys, it affords a good example of the precipitous nature of old roads.This enters the parish from Mawnan at Tregarne Mill, passes the steep hill to Treworval , by what is now a rough lane, continues across the fields to Driff and Treviades, then down past Gwealllin to the creek-head at Polwheveral. This part bore the name Clodgy lane in 1649, a common name in Cornwall, derived, in all zbability, from Clud, a carriage, or perhaps from Clodding, meaning trenched ” or “ embanked5.” At the bottom stood two grist mills, d • Tucking or Fulling Mill. The bridge over the stream was built as appears from the contract between the parish and Roger Urd, a mason, of Tregoney, entered into the old Vestry Book .

It appears to continue on the other side of the river through Tremayne and Henforth ( =Old road ) to St. Martins. ‘, Clodgy lane at Helston. Mr. Henderson later changed his mind, and Came to the conclusion that Clodgy meant a Lazar-house. a copy of this interesting document in the present writer’s Old Cornish Bridges,