why not the River Avon

Well, I think Eric Hemery is right when, in the pages of High Dartmoor, he quotes a moorman who suggests that Aune or Auna should be the name of this pretty river, given that there are lots of Avons and only one Aune. So let’s call it Aune on Dartmoor, though it might be the Avon as it winds a gentler course through the South Hams.

Aune Head defines Dartmoor for me. A little while ago I was asked to write a piece for an anthology on a wild place that defines Dartmoor. After some deliberation I chose Aune Head, given that it is unspoiled and not usually very crowded. I often ponder on the tinner’s hut there, imagining the man who must have lived and worked in that solitary place. The great mire is vast and untouched for all his efforts, with the cry of the curlew being one of the few sounds to break into the great silence.

In the early summer the skylarks fill the air round about, and a lonely heron might flap overhead.

Boggy ground it is too if you choose to explore in search of the exquisite mire flowers. A slight trudge through the mud on its edge reveals the Luckombe Stone, that great boulder that seems pointless in the landscape, yet somehow completes the view.

It must have all been a familiar scene to the traders and hucksters who used the nearby Sandy Way to get to the market at Princetown’s War Prison so that they might barter with those incarcerated French and Americans two centuries ago. Sometimes, if you lie on the edge of the mire and close your eyes, it seems as though you can almost hear the gossip of those ancient travellers above the soughing of the breeze through the moorgrass.

When I was a small child, this was only a country of the imagination for me. My first contact with the Aune was a childhood picnic at Shipley Bridge. Wandering away from the others I climbed up to Black Tor and looked northwards to these distant and yet to be explored hills. A few years later I spent my first night bivouacking without a tent on Dartmoor, in a hollow on the hillside opposite Huntingdon Warren.

The Aune has some of the best bathing pools on Dartmoor, many of them a few minutes stroll up from Shipley. We used to bathe in the Aune’s chill waters, dousing our heads under the many little waterfalls where the river tumbles through Long-a-Traw (Long Trough). We would sunbathe ourselves dry, turning the pages of William Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor, before continuing our exploration of the Moor. Sometimes we would meet and talk with Brother Adam of Buckfast Abbey, who kept his bees here to bring the taste of the moorland heather to the famous honey.

Long-a-Traw is one of the finest valleys on Dartmoor, ruined only by the dreadful concrete of the Avon Dam (and I revert to Avon for the name of this appalling intrusion) towards its head.

I mourn for the archaeology that was lost when the reservoir was built. More might go yet, for the dam was designed to be raised if circumstances made it necessary. To imprison a moorland river behind a dam, letting it pass only in fits and starts is a crime against nature.

Still, archaeology remains and one of my favourite areas is Rider’s Rings, a perfect place for a rest on a summer walk, though I do hope the bracken will be tackled soon. I like the little clapper bridge on the Aune above Huntingdon Cross.

I have stopped here for lunch on countless occasions, both on my own and with considerable numbers of Dartmoor walkers, fellow spirits in discovery, many of them now sadly passed on.

The focus for walks was often Broada Falls, that great mass of boulders through which the river forces its waters on the first stretch of its journey from Aune Head. I can remember, on one of my earliest visits, the late and much-missed Dartmoor expert Joe Turner showing me the ancient stone vermin traps just a little downstream.

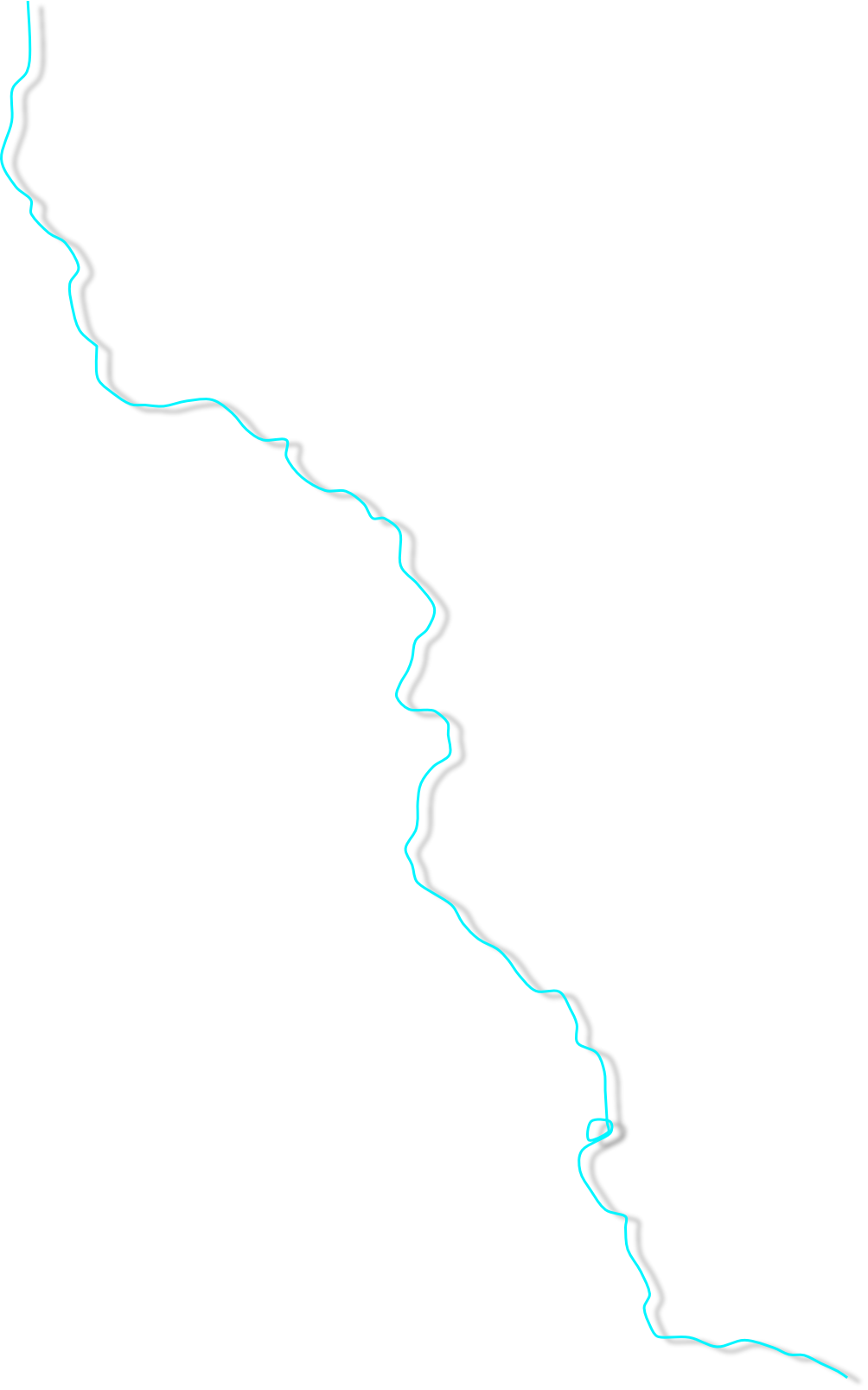

From the high hills around, the slopes of Huntingdon Warren or the White-a-Barrows, the Aune winds through the land like a blue ribbon against the yellow, brown and green of the surrounding moorland, as it reflects the blue of the sky on summer days. I have seen it as a sprawl of raging white foam after prolonged Dartmoor thunderstorms, though that is rare, for despite a fairly rapid descent the Aune is a gentle river. Above the reservoir it is quintessentially a high moorland river, free of much vegetation beyond the occasional overhanging rowan.

Below the reservoir the trees creep in to the landscape, with rhododendrons in the lower stages. I always think it a pity that Brent Moor House has gone, just a few low walls to mark its passing. I used to know a lot of moor folk who remembered it, and a few walkers who had stayed there during its brief incarnation as a youth hostel. Nearby, hidden high in the bushes, is the memorial to the young daughter of the Meynell family, killed when out horse riding in 1865.

Shipley Bridge is fortunate in that it stands some yards away from the nearby car park, thereby having its ancient view preserved without too much 21st century intrusion.

But even though the river ceases to be a moorland water at this point, I think we should continue our journey down through Didworthy, using the public right of way, to Lydia Bridge and then South Brent, where the Aune leaves the National Park.

I always think Lydia Bridge is one of the delights of Dartmoor and is too seldom visited. And what a beautiful name. South Brent should be visited too, not least as a homage to William Crossing who lived and explored Dartmoor from this useful base, using the valley of the Aune as an approach to so much of Dartmoor.

The Aune is a beautiful river and it is a privilege to walk here in the footsteps of Dartmoor’s greatest writer, the incomparable William Crossing.