io8 SOCIAL LIFE IN ENGLAND

CHAPTER XXXII Markets

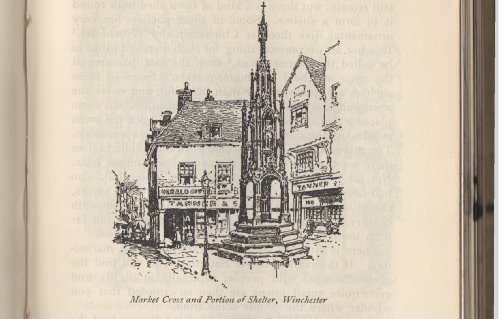

One of the pleasantest sights, to a Londoner at any rate, is the market-

A good many towns have built covered markets. Some of them are near the old market-

Corn-

The market-

MARKETS

many of these old buildings have been pulled down to make way for larger structures, in which the town can carry on its business, and where the various officers can have their offices, that the town hall is mostly now a smart modern building.

109

The stalls set up on the market-

Brass and Bronze.

So much similarity is observable in the modes of or ef working in the different combinations of copper with other metals, that the same description will apply pretty accurately to all of them.

In brass founding and before working, for instance, the making of the moulds, the melting of the metal in furnaces , the casting and subsequent trimming and finishing, the rolling into sheet , pr ht the drawing into wire— all are conducted pretty nearly in the same way as for other metals.

The making of the the brass itself is, however, rather a delicate operation.

This metal consists of about two parts of copper to one cuay of zinc ; the proportion not being exactly equal in all specimens.

In the first place the copper is melted, then and poured into cold water, by which it is made to separate into small pieces varying from the size of a small shot , to that of a bean, and known as “ shot-

The mi to zinc is produced from a carbonate of the metal, called Cung “ calamine;”

this is broken into small pieces, heated to redness in a furnace, reduced to a fine powder, and m; rm washed . Any quantity of the powdered calamine is then mixed with three-

The mixture is exposed to a strong heat in earthen crucibles for several hours ; at the end of fir elt which time the two kinds of metal have combined celys together in a liquid state, and the charcoal has disap-

- (on Mr. Westmacott’s plan), gun-

metal, with 30 per b( ? a I cent, of pure copper added to it. pi ice i The mode of proceeding in casting a bronze statue is is ill. much the same in principle as that of casting large bells, af ; is but with greater precautions in every part of the ope- T :er ration. - The making of the original model belongs to its [ry ! the highest department of art; for it is here that the ra or : sculptor show’s his consummate skill, by imparting to ei m-

the lifeless clay almost a living expression : all beyond si: he this, although requiring a very high degree of care, is at ?e- still mechanical, and governed by mechanical rules. to

annoyance and disappointment.

At length his labours seemed to be nearly at an end ; his mould was lowered into the pit, the furnace heated, and the metal thrown in. At this time, while a violent storm raged without, the roof of his study, as if to increase the confusion, caught fire; but, though ill and harassed, lie still directed the works and encouraged his assistants, till overcome by anxiety and fatigue he retired in a raging fever to lie down, leaving instructions respecting the opening of the mouth of the furnace and the running of the bronze.

He had not, he says, been reposing very long before one came running to him to announce evil tidings : the metal was melted, but would not run. He jumped from his bed, rushed to his studio like a madman, and threatened the lives of his assistants, with, being frightened, got out of his way till one of them, to appease him, desired him to give his orders, and they would obey him at all risks.

He commanded fresh fuel to be thrown into the furnace; and presently, to his satisfaction, the metal began to boil. Again, how-

Coining.

- The process of coining may, in some respects, be ranked among those here treated; for copper is the metal most largely used for this purpose, though its intrinsic value is much less than that of the silver and gold employed. The metal for such purposes is in the first instance rolled out to the state of sheets; these sheets are cut up into blanks, and the blanks are stamped on both sides at once, by means of hard steel dies, one to give each side of the impress. A curious record of past times has been dug up among the Roman remains in Britain, viz., a sort of coin-

mould or coin- die (Fig. 1083). This seems to consist of twro dies, one to give each side of the impress to a coin; the twro are so hinged together as enable the one to be brought down on the face of the other. Supposing a blank piece of metal to be placed between them, a smart blow from a hammer wrould give the double impress of a coin to it; but if metal in a semi- solid state (such as a soft kind of metal occasionally employed to produce “ cliche” medallions) were used, a slight pressure would suffice to give the impress. In another cut (Fig. 1089), copied from an old German print, a curious representation is given of a party of men busily engaged in coining, as it wras conducted in the rude style of former days. There is a furnace, containing the crucibles in which the metal is being melted; a man is hammering the cast metal into sheets ; another cutting the metal w ith a pair of shears ; another stamping by means of the die, aided by a boy; while the master- coiner, giving instructions to an assistant, seems to be keeping an account of the whole arrangements. The process of coining in the Mint of London is very different indeed from the above, and is considered to be unequalled in any other country. The metal is first brought to the state of oblong bars, and the processes which then follow are thus given in ‘ London/ No. 53 :— “ The bars, in a heated state, are first passed through the breaking- down rollers, which by their tremendous crushing powrer reduce them to only one- third their former thickness, and increase them propor- tionably in their length. They are now passed through the cold rollers, wdiich bring them nearly to the thickness of the coin required, when the last operation of this nature is performed by the draw- bench—a machine peculiar to our Mint, and which secures an extraordinary degree of accuracy and uniformity in the surface of the metal, and leaves it of the exact thickness desired. The cutting- out machines nowr begin their work. There are twelve of these engines in the elegant room set apart for them, all mounted on the same basement, and forming a circular range. Here the bars or strips are cut into pieces of the proper shape and weight for the coining- press, and then taken to the sizing- room to be separately w eighed, as w'ell as sounded on a circular piece of iron, to detect any flaw's. The protecting rim is next raised in the marking- room, and the pieces after blanching and annealing are ready for stamping. The coining- room is a magnificent looking place, W'ith its columns and its great iron beams, and the presses ranging along the solid stone basement. There are eight presses, each of them making, when required, sixty or seventy (or even more) strokes a minute; and at each stroke a blank is made a perfect coin— that is to say, stamped on both sides, and milled at the edge—