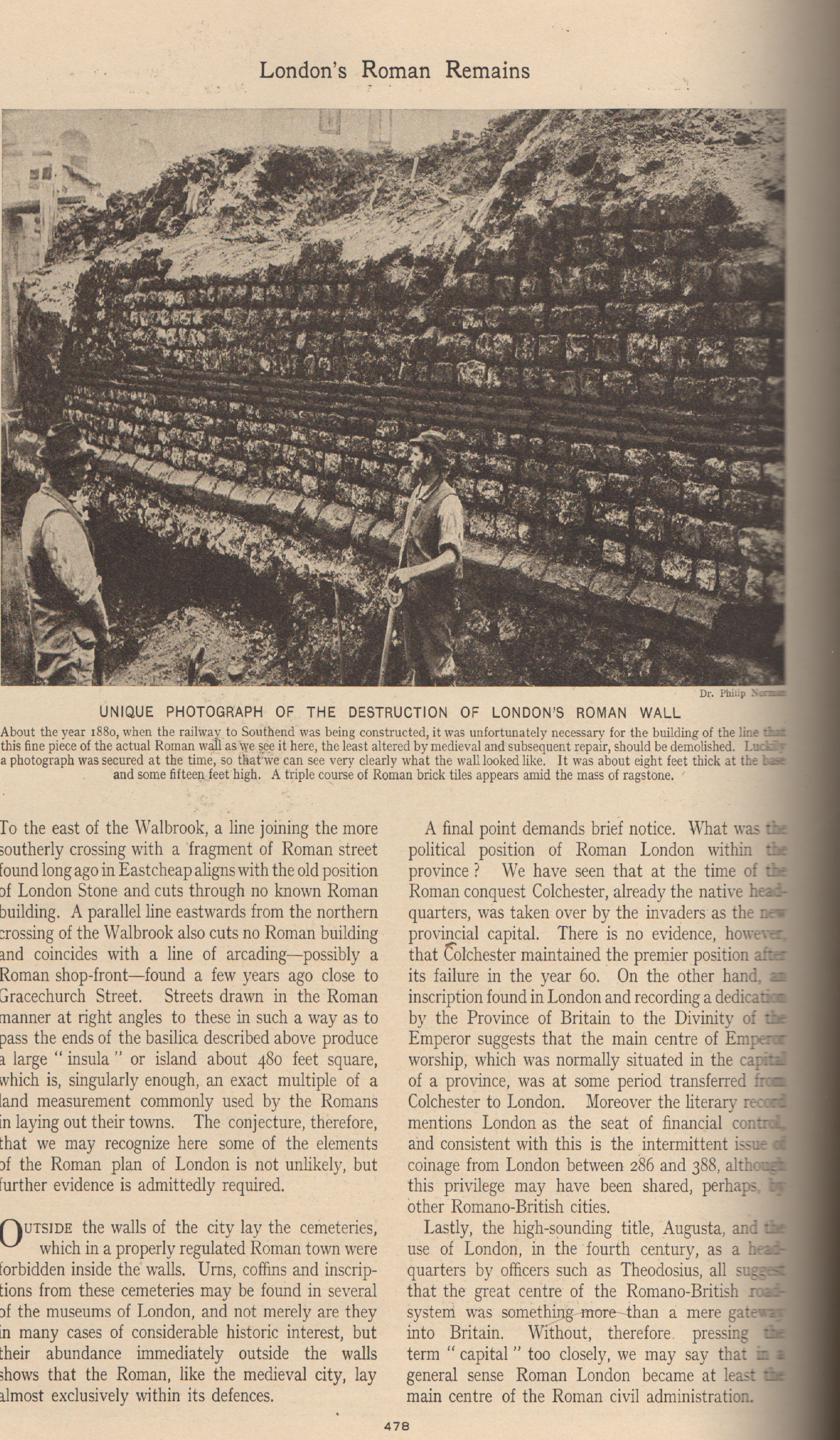

UNIQUE PHOTOGRAPH OF THE DESTRUCTION OF LONDON’S ROMAN WALL

About the year 1880,

when the railway to Southend was being constructed, it was unfortunately necessary for the building of the line that this fine piece of the actual Roman wall as tye see it here, the least altered by medieval and subsequent repair, should be demolished.

Luckily a photograph was secured at the time, so that we can see very clearly w hat the wall looked like. It was about eight feet thick at the i-aat and some fifteen, feet high. A triple course of Roman brick tiles appears amid the mass of ragstone.

To the east of the Walbrook, a line joining the more southerly crossing with a fragment of Roman street found long ago in Eastcheap aligns with the old position of London Stone and cuts through no known Roman building.

A parallel line eastwards from the northern crossing of the Walbrook also cuts no Roman building and coincides with a line of arcading— possibly a Roman shop-front— found a few years ago close to Gracechurch Street.

Streets drawn in the Roman manner at right angles to these in such a way as to pass the ends of the basilica described above produce a large “ insula ” or island about 480 feet square, which is, singularly enough, an exact multiple of a land measurement commonly used by the Romans in laying out their towns.

The conjecture, therefore, that we may recognize here some of the elements of the Roman plan of London is not unlikely, but further evidence is admittedly required.

Jutside the walls of the city lay the cemeteries, which in a properly regulated Roman town were forbidden inside the walls.

Urns, coffins and inscriptions from these cemeteries may be found in several of the museums of London, and not merely are they in many cases of considerable historic interest, but their abundance immediately outside the walls shows that the Roman, like the medieval city, lay almost exclusively within its defences.

A final point demands brief notice.

What was the political position of Roman London within the province ? We have seen that at the time of the Roman conquest Colchester, already the native headquarters, was taken over by the invaders as the new provincial capital.

There is no evidence, however; that Colchester maintained the premier position after its failure in the year 60.

On the other hand, a2 inscription found in London and recording a dedicatica by the Province of Britain to the Divinity of the Emperor suggests that the main centre of Empercr worship, which was normally situated in the capital of a province, was at some period transferred tr:cL Colchester to London.

Moreover the literary recced mentions London as the seat of financial contral and consistent with this is the intermittent issued

coinage from London between 286 and 388, although this privilege may have been shared, perhaps, by other Romano-British cities.

Lastly, the high-sounding title, Augusta, and the use of London, in the fourth century, as a headquarters by officers such as Theodosius, all sue;esc that the great centre of the Romano-British road system was something more than a mere gate way into Britain.

Without, therefore, pressing rat term “ capital ” too closely, we may say that ia a. general sense Roman London became at least the main centre of the Roman civil administration.