ᚔ I Idad

'Yew-

sinem fedo

"oldest tree"

caínem sen

"fairest of the ancients" lúth lobair

"energy of an infirm person"

An Old Irish Joke in Primtive Irish (translation by David Stifter)

Transliteration

Tengwās īwerijonākā

Tut raddassodd trīs dītrebākī dīslondetun do bitū.

Tēgoddit in wāssākan do atareregiyī esyan kenutan writ dēwan.

Bāddar kina labarātun writ alaliyan qos qennan blēdaniyās.

Issit andan esset bīrt wiras dī ēbis writ alaliyan diyas blēdniyas: “mati ad tāyomas.”

Bowet samali qos qennan blēdaniyās.

“Issit mati sodesin,” esset bīrt aliyas uiras.

Bāddar andan ēran sodesū qos qennan blēdaniyās.

“Tongū wo mō brattan,” esset bīrt trissas uiras, “ma nīt lēggītar kiyunessus do mū, imbit gabiyū wāssākan oliyan dū swi.”

Old Irish (Sengoídelc) version

Tríar manach do·rat díultad dont ṡaegul.

Tíagait i fásach do aithrigi a peccad fri día.

Bátar cen labrad fri araile co cenn blíadnae.

Is and as·bert fer diib fri araile dia blíadnae, “Maith at·taam,” olse.

Amein co cenn blíadnae.

“Is maith ón,” ol in indara fer.

Bátar and íar suidiu co cenn blíadnae.

“Toingim fom aibit,” ol in tres fer, “mani·léicthe ciúnas dom co n-

Modern Irish (Gaeilge) version (by Dennis King)

Triúr manach a thug diúltú don saol.

Téann siad ins an fhásach chun aithrí a dhéanamh ina gcuid peacaí roimh Dhia.

Bhí siad gan labhairt lena chéile go ceann bliana.

Ansin dúirt fear díobh le fear eile bliain amháin ina dhiaidh sin, “Táimid go maith,” ar seisean.

Mar sin go ceann bliana.

“Is maith go deimhin,” arsa an dara fear.

Bhí siad ann ina dhiaidh sin go ceann bliana.

“Dar m’aibíd,” arsa an treas fear, “mura ligeann sibh ciúnas dom fágfaidh mé an fásach uile daoibh!”

English version (by Dennis King)

Three holy men turned their back on the world.

They went into the wilderness to atone for their sins before God.

They did not speak to one another for a year.

At the end of the year, one of them spoke up and said, "We’re doing well."

Another year went by the same way.

"Yes we are," said the next man.

And so another year went by.

"I swear by my smock," said the third man, "if you two won’t be still I’m going to leave you here in the wilderness!

The Isle of Man may be a small and -

One of the legacies of this battle for dominance were the keeills -

All, that is, except one which has lain protected beneath the seventh fairway of the Mount Murray golf course, marked only by a patch of unkempt grass and a single standing stone atop a small mound. Time Team was given the unique opportunity to excavate the only known untouched keeill remaining on the Isle of Man.

Category

Education

Ogham (᚛ᚑᚌᚐᚋ᚜)

Ogham is an alphabet that appears on monumental inscriptions dating from the 4th to the 6th century AD, and in manuscripts dating from the 6th to the 9th century. It was used mainly to write Primitive and Old Irish, and also to write Old Welsh, Pictish and Latin. It was inscribed on stone monuments throughout Ireland, particuarly Kerry, Cork and Waterford, and in England, Scotland, the Isle of Man and Wales, particularly in Pembrokeshire in south Wales.

The name Ogham is pronounced [ˈoːm] or [ˈoːəm] in Modern Irish, and it was spelt ogam and pronounced [ˈɔɣam] in Old Irish. Its origins are uncertain: it might be named after the Irish god Ogma, or after the Irish phrase og-

Ogham probably pre-

While all surviving Ogham inscriptions are on stone, it was probably more commonly inscribed on sticks, stakes and trees. Inscriptions are mostly people's names and were probably used to mark ownership, territories and graves. Some inscriptions in primitive Irish and Pictish have not been deciphered, there are also a number of bilingual inscriptions in Ogham and Latin, and Ogham and Old Norse written with the Runic alphabet.

Notable features

Type of writing system: alphabet

Number of letters: 25, which are grouped into five aicmí (sing. aicme = group, class). Each aicme is named after its first letter. Originally Ogham consisted of 20 letters or four aicmí; the fifth acime, or Forfeda, was added for use in manuscripts.

Writing surfaces: rocks, wood, manuscripts

Direction of writing: inscribed around the edges of rocks running from bottom to top and left to right, or left to right and horizontally in manuscripts.

Letters are linked together by a solid line.

Used to write: Primitive and Old Irish, Pictish, Old Welsh and Latin

The Ogham alphabet (vertical)

The pronunciation of the letters shown is for Primitive Irish the language used in the majority of Ogham inscriptions. The names and sounds represented by of the letters uath and straif are uncertain. There are many different version of the letter names -

The Ogham alphabet (horizontal)

Downloads

Download a Ogham alphabet chart in Excel, Word or PDF format

Sample texts in Ogham

Texts in Primitive Irish

Transliteration

LIE LUGNAEDON MACCI MENUEH

Translation

The stone of Lugnaedon son of Limenueh

From: Inchagoill Island, County Galway, Ireland

Ogham stone form Mount Melleray in County Waterford in Ireland.

Transliteration

Na Maqi Lugudeca Muc Cunea

Translation

The Sons of Lugudeca, Son of Cunea

Source: http://www.prehistoricwaterford.com/news/the-

An Old Irish Joke in Primtive Irish (translation by David Stifter)

Transliteration

Tengwās īwerijonākā

Tut raddassodd trīs dītrebākī dīslondetun do bitū.

Tēgoddit in wāssākan do atareregiyī esyan kenutan writ dēwan.

Bāddar kina labarātun writ alaliyan qos qennan blēdaniyās.

Issit andan esset bīrt wiras dī ēbis writ alaliyan diyas blēdniyas: “mati ad tāyomas.”

Bowet samali qos qennan blēdaniyās.

“Issit mati sodesin,” esset bīrt aliyas uiras.

Bāddar andan ēran sodesū qos qennan blēdaniyās.

“Tongū wo mō brattan,” esset bīrt trissas uiras, “ma nīt lēggītar kiyunessus do mū, imbit gabiyū wāssākan oliyan dū swi.”

Old Irish (Sengoídelc) version

Tríar manach do·rat díultad dont ṡaegul.

Tíagait i fásach do aithrigi a peccad fri día.

Bátar cen labrad fri araile co cenn blíadnae.

Is and as·bert fer diib fri araile dia blíadnae, “Maith at·taam,” olse.

Amein co cenn blíadnae.

“Is maith ón,” ol in indara fer.

Bátar and íar suidiu co cenn blíadnae.

“Toingim fom aibit,” ol in tres fer, “mani·léicthe ciúnas dom co n-

Modern Irish (Gaeilge) version (by Dennis King)

Triúr manach a thug diúltú don saol.

Téann siad ins an fhásach chun aithrí a dhéanamh ina gcuid peacaí roimh Dhia.

Bhí siad gan labhairt lena chéile go ceann bliana.

Ansin dúirt fear díobh le fear eile bliain amháin ina dhiaidh sin, “Táimid go maith,” ar seisean.

Mar sin go ceann bliana.

“Is maith go deimhin,” arsa an dara fear.

Bhí siad ann ina dhiaidh sin go ceann bliana.

“Dar m’aibíd,” arsa an treas fear, “mura ligeann sibh ciúnas dom fágfaidh mé an fásach uile daoibh!”

English version (by Dennis King)

Three holy men turned their back on the world.

They went into the wilderness to atone for their sins before God.

They did not speak to one another for a year.

At the end of the year, one of them spoke up and said, "We’re doing well."

Another year went by the same way.

"Yes we are," said the next man.

And so another year went by.

"I swear by my smock," said the third man, "if you two won’t be still I’m going to leave you here in the wilderness!

Texts in Latin

Transliteration

Numus honoratur sine. Numo nullus amatur.

Translation

Money is honoured, without money nobody is loved

From: The Annals of Inisfallen of 1193

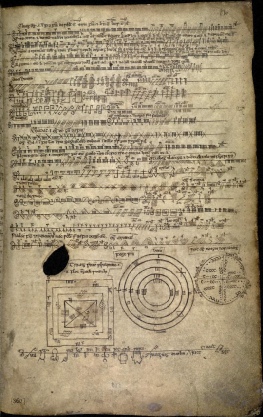

From: The Book of Ballymote (Leabhar Bhaile an Mhóta), written in 1390 or 1391.